Looking for the Politics of Happiness in Contemporary Democracies

Experts say that democracies across the globe are turning increasingly “authoritative” especially for people of marginalized backgrounds

Credits: Marija Zaric

July 22, 2022

Do you ever feel estranged from your country’s politics? Do you choose not to cast a vote, or engage in political discussion because you think your individual voice has no power to bring about any significant change in the ‘system’? If so, you’re not alone in feeling this way. Voter turnout rates are declining in democracies around the globe.

Described often as a form of government ‘of the people, by the people, for the people’, the democratic system faces a great existential threat with the very people growing apathetic towards the system they created for themselves. Through its unique ability to facilitate negotiation and compromise, democracies have allowed many disputes around the globe to be resolved in a much-appreciated non-bloody manner. Democracy allows us to give power into the hands of those who (the people think) are most deserving. However, what does it mean when one does not choose to vote? It could perhaps mean that there existed not a single candidate that the individual deemed worthy of incumbency.

As discouraging as that might be, it is a feature of democracy. Some countries, like Indonesia, allow for a ‘none of the above (NOTA)’ voting option for their citizens to have their non-preference represented. Unlike India, the option NOTA in Indonesia is not merely for the sake of it – it has power. When a sole mayoral candidate received lesser votes than the NOTA option in Indonesia, it led to the entire election being held again. Other than no preference, the other, more worrisome reason for an individual not voting would be them believing that their vote has no power. i.e., believing that even if they went out and cast their vote, it would lead to no desirable change in society. To use a more technical term, we could say that the individual lacks political efficacy.

However, not going out to vote is not all that not having political efficacy entails. It consists to all possible political activities. Avoiding the news, not going out to protest against policies that they find troublesome, and refraining from engaging in political discussions are some other behaviours that one might exhibit. It refers to the fleeting feeling that it is not worthwhile to perform one’s civic duties.

Credits: Phil Scroggs

Women living under authoritative regimes – such as Yemen, where they face forced child marriage, divorce shaming, domestic violence, and even occasional honour killings by the hands of their patriarchal male ‘guardians’ are living testaments to this phenomenon.

So why do we see this phenomenon? What leads to a citizen feeling this way?

One of the more obvious reasons that one can think of is their background. An individual’s social circles, upbringing, parents, race, caste, educational background, and religious affiliations play a major role in determining their actions (or inactions). For example, a 1970 study in a small US city found that being a black youth was a strong indicator of cynicism. Black youth reported feeling less efficacious than their white counterparts. By the end of middle school, black children had been socialized into a level of cynicism that white students did not face until the beginning of their high-school years. Furthermore, black children also developed negative feelings towards the government long before adolescence. Naturally, their cultural, social, and racial background played a major role in determining their political efficacy. Political scientists know this as the process of political socialization.

So how does one predict a country’s level of political participation? Given that political socialization is such an individual, micro-level process – it is significantly difficult to measure and hence cannot be used to predict political participation at a macro-level. A related, but distinct from efficacy (self or political) is the concept of happiness. If we look back to examples of black kids in the US small-town and the chronically repressed women in Yemen, what can we say that these two groups have in common?

Credits: Hanna Zhyhar

While the socio-economic backgrounds of both differ significantly, it won’t be unreasonable to say both these populations are deeply unhappy.

Constant discrimination and denial of rights are bound to make citizens unhappy. So, is a happier country more likely to be more politically active? And if so, can happiness be measured at a macro-level? The answer to the latter, is yes.

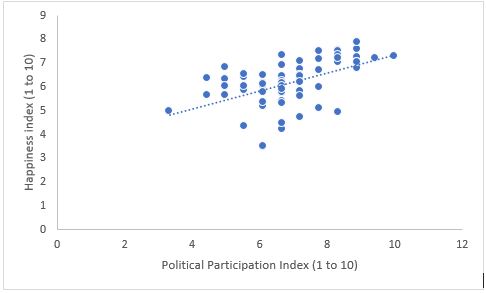

The World Happiness Index has indexed countries across the globe according to their citizen’s happiness using various measures. And as for finding the answer to the first question, we graphed the World Happiness Index (WHI) of 75 democratic nations against their level of political participation (as defined in The Economist annual Democracy Index, 2020). This was the result:

The Pearson’s correlation between the two indexes was 0.512. In simpler terms the happier a country’s people were, the likelier they were to be politically participative!

These findings may seem obvious when stated, but they give us key indicators of what policymakers should watch out for when discussing political participation.

The WHI looks at a total of 11 indicators when measuring happiness, namely – GDP per capita, GINI Index, perceptions of subjective well-being, positive affect, negative affect, social support, institutional trust, corruption perception, freedom to make life choices, healthy life expectancy, and generosity.

It is not unreasonable to assume that improving upon these factors will increase political efficacy of a country’s citizens. The question now is whether incumbents are keen on improving in these areas, and how they decide to go about achieving them!

Author bio: Harshiv Chhabra is an intern at Jindal Institute of Behavioural Sciences.

Additional editorial inputs from Samreen Chhabra